Medical terminology is everywhere. Whether you live in South Korea or Nigeria, every language employs terminology for human body parts, conditions, cures and healthcare professions, some native and some adopted through contacts or scientific advancements and new technologies. Globalization opens the further way for sharing good practices and findings, introducing novel medications and integrating state-of-the-art medical devices — both for therapeutic and diagnostic use, not only for profit, but to battle global crises. The COVID-19 pandemic alone created an explosion of innovative laboratory diagnostics and immunization solutions desperately needed by people everywhere. To make such solutions available worldwide, we must turn to medical translators.

But why are there so few of them? Is it due to the complexity of topics, weight of the responsibility, or difficult jargon? We’d say all of the above. But jargon is a language and language could be learned. With the right approach.

Medical terminology is a system of terminologies. The Medical Field concept spans many subject matters, industries and professions, each having their own language. Moreover, there are different lexica for — to name a few — human anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, genetics, diseases, signs and symptoms, diagnostic, therapy and intervention methods, devices and disposables, healthcare institutions and respective organizational structure, etc.

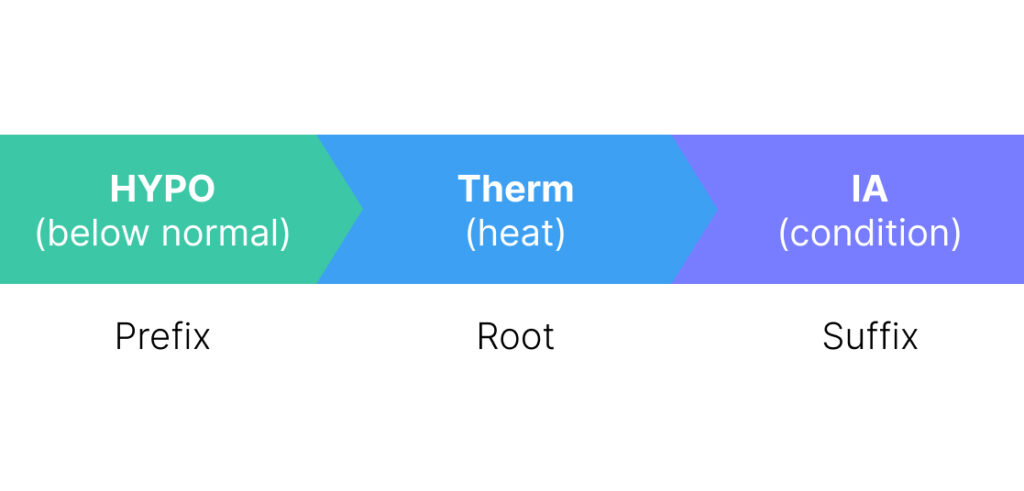

Speaking of medical terminology, one usually means two groups of international terms: anatomical and nosological, both mostly Latin and Greek in origin. Such terms are “constructed” from the special group of roots and affixes — each adding one unambiguous meaning — highly recognizable across writing systems and grammars (especially Western ones).

For example, “hypo + therm + ia” means “below normal + temperature + condition”, and “vagotomy” is the EN spelling for “vago + tomia” which is “vagus nerve+cutting”.

Such terms are regulated by international and local agencies. Some of them — termini technici (technical terms) — are customarily used only in Latin, like widely known in vitro and in vivo.

But that is not all.

Each smallest medical device, every part of sample tube, every step in quality control, and every condition of sterilization has its own name. The origins of these terms vary. Some connections could be traced back to historical circumstances (e.g., orthopedic surgery tools being similar to carpenter tools), for others, the underlying logic is not so easy to deduct.

Being the natural language, “medical talk” is also subject to various fluctuations, especially in small or semi-isolated professional circles, like companies and hospitals. Such jargon rarely enters the general medical lexicon but is no stranger to spontaneous speech and semi-spontaneous clinical texts like, for example, health records.

Additionally, it should be noted that not all medical terminology is “medical”. Quite a number of life sciences texts are interdisciplinary in nature. To translate a user guide for an automated blood counter one must be knowledgeable not only in types of cells, reagents and lab procedures, but also in hardware, software and electrical safety. Translation of medical visualization software requires understanding of computer graphics. In clinical trials statistics is a must. Seemingly simple health plans contain insurance terminology. And we can go on.

Pretty complex, isn’t it?

Our heroes are called medical translators and medical interpreters.

The former work mostly with prepared written medical documentation spanning product leaflets, user guides, information and marketing brochures, clinical trials documentation and questionnaires, electronic health records, adverse event reports, user interfaces for hospital and portable medical devices, subtitles for healthcare-related video, etc. The latter — with spontaneous speech on site (at events, meetings and talks, at the point of care, etc.) or remotely.

Their job is to break down language barriers and bridge semantic gaps between diverse groups of communicants — medical device manufacturers and health professionals, clinical trial staff and enrolled participants, pharmaceutical companies and regulatory agencies, guest speakers and medical students, physicians and patients, and so on.

To provide the highest level translation services, such professionals should not only demonstrate competencies stated in applicable standards (e.g., ISO 17100), but be precise, patient, and kind. And, of course, they should be able to confidently operate medical terminology both in source and target languages, choose appropriate words for targeted audiences and skillfully resolve any terminological issues.

There are a lot of terms. Terminologia Anatomica alone contains over 7000 terms for human anatomical structures. UMLS Metathesaurus contains about 17 million concept names. No one could know and — most importantly — correctly operate them all.

According to St. George’s University research, there are about 20 major medical specialties. This count can vary in different countries depending on the healthcare system. Some of them are so very far one from another (e.g., endocrinology, dentistry, and radiology), that switching between them requires a great deal of knowledge, many years of translation experience, and good terminology management.

Many Graeco-Latin medical terms have absolute or partial synonyms, either loaned from another language or native (e.g., ictus, stroke, seizure). Additionally, in clinical practice, it is common to use synonymous truncated words (influenza – flu), and some terms are accompanied by eponyms (shaking palsy – Parkinsons disease).

Synonyms also function as “laymans terms” that are used mostly by non-professionals (e.g., furuncle – boil). Such bilingualism exists both in source and target languages and is essential to be kept in mind for patient-oriented communications such as in the course of clinical trials, to ensure complete clarity.

To save precious time, medical experts use abbreviations. It could be shortened words (temp.) or acronyms either from first letters of words (rapid eye movement – REM) or syllables (intravenous – IV). Some of them are unrecognizable out of context (ventricular tachycardia – V tach), and some have different meanings depending on it (MI – myocardial infarction – mitral insufficiency).

Meanings of such terms never should be guessed. Translating them often requires sending a query to the author.

The target country can have an established tradition regarding terms and practices, for example, in classification of structures or substances. Some classifications, like insulin types (rapid-acting, short-acting, intermediate-acting, long-acting, ultra-long-acting) could be incomplete or lack the approved translations or have too many variants (like, male and female Luer Lock in Russian). Some polysemous terms, like forceps, could have different translations depending on type and size (clamp, pincers, kornzang). Sometimes even the classical terminology gets ambiguous. For instance, clear logical differentiation between – isis (inflammation) and – osis (non-inflammatory condition) breaks with the term “arthrosis” which is called “Arthrose” in German and “osteoarthritis” in English.

Together, all these challenges make navigating multilingual medical terminology akin to navigating uncharted waters by moon, stars, weather signs and undercurrents.

Narrow your field of expertise (e.g., diabetes management) to reduce the volume of terms to harness. Do not rely on dictionaries alone, be sure to familiarize yourself with applicable standards (they often include definitions), articles in ICD-11 and corresponding articles in your native languages. Research industry ontologies and thesauri. Follow clinical trials — all materials for participants undergo rigorous quality check and can be trusted. Accumulate all the knowledge into glossaries and terminology bases.

Words are fluid, shapes and indications are usually not. Search for a picture for every device and disposable, video for every action, photo for every symptom and reaction. Be sure to check every anatomical structure in anatomical atlases. Organize all references, create a clear structure, plan the simple search algorithm to be able to refer to them at any time. Find a way to link the images to glossaries or add them to the term base to save time later.

As was said before, Graeco-Latin terms follow clear logic. Mastering it takes time, but is more effective than memorizing. Other terms often have roots in standard language and partially share the common meaning. Metaphors and metonymy are as natural to medical language as to any modern language. And, most importantly, every system has its inherent rules, term systems included.

Link every new term into a system and do not forget to reflect it in your glossaries.

Healthcare is not theoretical. Try to understand not only the verb, but what is done, how it’s done, why it’s done, who is doing it. Choose a couple of theme blogs and follow them, check manufacturers sites, subscribe to specialized medical journals, monitor papers on PubMed and WHO multilingual publications.

Listen. Patients’ conversations in hospital queues are an invaluable source of lay terms. And do not forget to update the glossaries with new data and useful comments.

Medical area is not a playfield. Though not all mistakes could harm patients, even the smallest possibility should be eliminated. However reliable the medical dictionary you use, however experienced you are, any ambiguity should be resolved with the author of the text and/or actual medical expert. Establish good working relationships with medical specialists and keep them on the speed dial, write down every answer into the well-structured query base, and update the glossaries immediately — to save every bit of priceless knowledge your colleagues share with you.

In addition to industry resources listed in the text above, we advise you to refer to online resources that may help you to operate medical terminology more smoothly:

Medical translation is a task that requires a high skill in at least two languages, a deep understanding of terminology and underlying concepts, and expertise in the narrow medical field. Finding a translation agency that matches all the criteria is a challenge in itself.

Palex team has extensive experience working with companies engaged in pharmaceutical, Life Sciences and medical fields. To provide the highest quality services, we work with a global net of language professionals and experts involved in multiple fields. Contact us to get a free quote — we are looking forward to working with you.